Yes. But.

Unless you lived on some remote electricity void mountain located in some impossibly pronounced country like Arstotzka” (*ahem,* your papers please) then you must have heard the word Skyrim at least once in your life, even if it was whispered out of the mouths of a huddle of the deepest darkest nerds in your frequented place of gathering. Skyrim, took the gaming world by force and its influence is so incredibly powerful that in spite of it being six years old, Bethesda is in no hurry to release the sixth Elder Scrolls game, instead re-releasing the fifth one twice. Ask your average gamer if Skyrim is good and you’ll get a resounding “YES!” from not just the person you asked but also anyone else in the room who’s played the game. I suppose that makes Lepcis and I the un-average gamer, since we might respond with, “Yes but–” There is always a but. Is the world incredibly large? “Yes but–” Does the player have complete freedom over how they level up their character? “Yes but–” Are there tons of magical monsters and creatures? “Yes but–” Are there countless quests and dungeons? “Yes. But.”

It’s difficult to critique this game, for any time you speak out against it, it seems foolish in consideration of the mountain of content that the game presents. A critic of your critique may sarcastically respond “Oh, I’m sorry over 1,000 NPCs wasn’t enough for you,” or “I’m sorry you got bored doing over 400 quests spanning hundreds of hours of content.” The fact is, trying to say anything bad about Skyrim is almost like trying to file a complaint with Mother Theresa–something that is well within your right to do I supposed, but very hard to make stick.

However, I am here to submit that very statement to you. I am here to tell you, that Skyrim in many glaring ways is not a good game. You may disagree with me–and that is completely valid. You may overlook the issues I have with the game and frankly, your tastes may just be different than mine. In spite of this, whether you agree with me or not, I hope to make pleasant conversation, bringing light to several aspects of the game that I find fault with, that ultimately would lead me to not recommend this game to anyone, placing it into Tier 3.

(*sigh* Fine, here’s the obligatory caveat dammit; if you have access to mods, then the game is a clean Tier 1 but shutup you, those don’t exist for now.)

As it stands, I am a much more a mechanics/immersion driven player, and as such I shall focus more on these topics while I discuss the game. Skyrim is complex enough that you could write an entire book on the subject (considering that Skyrim itself also has several “books” written within it as well) so it helps to limit the scope for the sake of conciseness. If, however, you wish you read up on a viewpoint differing from mine, Lepcis approaches the game from a much more narrative/lore angle found here. Otherwise, prepare yourselves for a primary analyses of Skyrim’s mechanics with a secondary overview of immersion.

Why are Mechanics Important?

Mechanics are important because they are a game’s differentiating characteristic from itself and other forms of media. Don’t get me wrong, a game often needs a good story, but a good story on its own is just that–a story. A game often benefits from attractive or stylistic visuals, but attractive or stylistic visuals on their own are just art. Similarly, a game needs a great soundtrack to rest in the back of everything that’s going on within the game, but a great soundtrack on its own is just music. A ball tied to string tied to a cup though? That is a game. A 3 x 3 grid to soon be filled in with X’s and O’s? That is a game. An empty recyclable bottle that is spun in a circle? This too, is a game. The fact is, that without a game’s mechanics–without the rules and the required objects governed by those rules–you don’t have a game, you have pictures or sound or words and so on. These things can be combined to add to a game and make a good game fantastic, but on their own they simply represent themselves. We often use the word “game” to imply the final product of all these things wrapped up into one bundle but truly the mechanics are the “game” part of the game. They are the part that is played. You can’t “play” art. You can’t “win” music. Therefore, borrowing from what was said above, we can make these two statements:

A game is a set of mechanics.

Game mechanics are the combination of a set of rules and the things governed by those rules.

In this way, a game can be about music if the music is governed by a set of rules, such as in Guitar Hero. Likewise a game can be about art if the art is governed by a set of rules, such as in Pictionary and so forth. Once again, music is not the game, nor is art, but the game’s mechanics can be structured around both. This has always been a point of my own contention when discussing “games” with people. Someone might tell me that “Her Story,” is a “good game.” Her Story is a terrible game–it barely qualifies as a point-and-click adventure, the mechanics are tedious after a while and there is no defined purpose for the player to fulfill. However, I would probably respond to the person I was talking to with, “Yeah, it was definitely an interesting game. I’m not quite sure what the message was, but it was a fun way to spend an hour.” You see, we actually aren’t talking about Her Story as a game at all, even though that’s how we’re referring to it. What we’re really saying is that Her Story is an engaging interactive media experience that we both enjoyed.

Over the years the definition of “game” has melted, similar to René Descartes’ famous “Wax Argument.” At what point does the melting wax of a candle set by the fireside cause it to cease becoming a candle? Likewise, at what point does the conjoining of various add-ons to a game cause it to cease being a game? Or even further; at what point does the very word we use to describe the idea of a set of rules and the things governed by those rules become false?

–Enter Rabbit Hole–

Now it is true that some might say, “But there are many rules and things that are governed by them that aren’t games.” Well, with the exclusion of Rules, or Laws, of Nature (“You win again gravity!“) do not all rules have a winner or a loser? Have we not taken the mundane rules of our world and turned them into a game? What is “Papers Please” if not a game about surviving the oppressive nature of a communistic government? What is “Cooking Mama” if not a game about preparing food? What is “Surgeon Simulator?” We don’t use language to describe it as such, but does a doctor not “win” if he saves his patient? Does an artist not “win” if she releases a successful album? Some may say, “Life is just a game,” to mean that everything is a joke and nothing matters but I say anyway, “Life is a game!” We have goals, objectives, quests, adventures, misadventures, setbacks, downfalls, struggles, obstacles and ultimately an ending. If “All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players,” then how are we not players of the world’s stage-like game?

At some point though, the concept of “game” became lost with the explosion of the gaming market. I will not sit here and argue with you that “The Stanley Parable” is a bad game. I will argue however, that calling the Stanley Parable a “game” is a misnomer. After all, it’s called a “walking simulator” for a reason–primarily all you do is move your perspective from one location of a slightly interactive world to another. Stated again, the conflict is that what we are talking about when we refer to the Stanley Parable is not a game but an “interactive media experience.” When I was five years old, I had a computer program that told a story if you clicked on enough of the little pictures to make it continue. I didn’t call it game, it didn’t call itself a game, and in fact, it wasn’t a game. Nowadays, products like this get released on Steam and the like all the time and word “game” is applied to them without a second thought.

–Exit Rabbit Hole–

So now return and answer the question “Why are mechanics important?” Why, because life is important! But realistically, it is because mechanics are the life of a game. They must be changed, adapted, filtered, mended, tempered, discarded and created in order for a game to thrive, just as a person must do the same things to themselves if they are to live in this world. Basketball is not the same game it was 50 years ago. Mario is not the same game it was 25 years ago. Even Chess, one of our oldest currently-played games is still technically changing. After all, the idea of playing chess against anyone across the world within a couple seconds without actually touching real pieces may have seemed like science fiction to our grandparents but today, we can do just that. This only creates very minor mechanical changes (there is no longer any argument concerning the “when your hand has left the piece” and you don’t have to physically “hit” a timer to end your turn, as the program does so automatically), but they are still changes nonetheless. Mechanics are important because they are the very structure of what a game is, spanning across and beyond human history. Without mechanics there can be no game. Without mechanics, there is no motivation, no goal–absolutely nothing at all.

Wasn’t This Supposed to Be About Skyrim?

You can probably see where I’m going with this, but yes, let’s look back at Skyrim. Skyrim may be an entertaining “interactive media experience,” but it is, at best, something that only simulates a game. Large portions of the “game experience” are artificial. Rules are communicated very poorly to the player, if they are ever communicated at all. Balance of the game’s mechanics range from mediocre to down-right awful. Counterplay in certain circumstances is almost completely removed. The worst part about it–the part that makes me grind my teeth the most when I try to critique this game–is that the world absolutely loves Skyrim and that worries me as a mechanics-devoted gamer. It worries me because I think that I must live in a world where my fellow gamer does not desire quality, only the illusion of quality. I feel alone in that instead of recognizing the falsehoods of easily accessed grandeur and inorganic replicated “challenges,” the majority of the gaming world wants to be spoon-fed their magnificence from a prosthetic arm.

Look, if I’m honest, there are plenty of crap games out there with bunk mechanics that offer immediate gratuity for less-than-authentic repetitive action. Sometimes you just want to play a game that gives you sword (or in my case a staff), puts you in a field with monsters and progressively gives you a bigger and bigger sword after you’ve wacked the monsters enough times. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with enjoying this kind of game as long as the player understands what’s going on. It’s sort of like a box of Little Debbie’s snack cakes. If you’re hungry, have a few dollars and are short on time, a box of corn-syrup, pre-processed flour, powdered sugar treats are probably going to be awesome. You would never make the claim that Little Debbies had somehow managed to reach the Nirvana of baking–you probably wouldn’t even claim that they were healthy for you or made of wholesome ingredients–but for what they are they taste good in small doses. The same can be said for games of the pre-described nature.

The problem is that Skyrim isn’t described, seen or even rationalized in this way. Instead it’s seen as this Nirvana, this golden pinnacle of gaming that somehow only the “best” games can reach and the rest must settle in the lowly dredges of non-accomplishment. The masses overlook its cardboard-cut-out nature, its shallow design. Sometimes I feel like a conspiracy theorist or a street-preacher when I complain about it. Enough though; I’ve done a lot of blabbering with little backup, so let’s get into the core of some the actual mechanics themselves so I can show you what I mean.

Questing – Show Don’t Tell

Quests are horrible. This may come as a bit of a shock to you, but I’m going to say it again. Quests. Of any kind. Are. Horrible. And this is why.

My favorite game to this day, is Lands of Lore II. I’m not sure whether it’s as good as I think it is, or if I developed a pseudo-Stockholm syndrome-esque attachment to it after doing nothing but locking myself up in my room and playing it for two weeks straight after the death of my father. Either way, I have so many good things to say about it. The world is beautiful, the characters are engaging and the plot is interesting. More than anything though, I loved getting lost in the world. The game never told you what to do or where to go. Well, I mean sure, there was a plot that gave general agency to the meaning of your actions but the best part about LoL II is just wandering around and discovering things that are hidden in clever and meaningful ways.

Sometimes the things discovered were big but oftentimes they are small. A lightning crystal hidden in the water here, a tiny cave exposed by draining a small pond there–outside of the game’s extremely light “tutorial,” every single thing you find in the game is your own. The game never points you towards any of it, save for the very clues to the puzzle’s answer themselves. Nowadays they would be considered “side quests,” but there are plenty of optional characters to talk to and little “quests” (by the definition of the word) that you can go on but at no point is a reward guaranteed or necessarily implied. The point of doing these quests was simply to discover more of the world. While the motivation to complete them may have been to discover what you’ll get out of it, the acquisition of a new thing was only secondary to how it was obtained. A skeleton key may be stolen from a fellow thief, a dagger may be given to a lost son, a charm may be unearthed from a locked temple; none of these things are mandatory in the game but upon doing them the game becomes more complex and more interesting.

How horrible LoL II would have been if each time something interesting happened, the game had to tell me that I should find it interesting. How horrible would it be if instead of being allowed to discover the interesting bits of the world, the game merely activated variables which gave me access to pieces of text which just laid out all the interesting parts of the locations I visited. The mystery of discovering new things would be lost. The control of being allowed to guide my own hand to my own destiny would be gone. The thrill of finding a new way to solve a quest that you thought was binary would evaporate. “Quests,” as they commonly exist in modern day games ruin large portions of what makes a good game by falling into the trap of telling instead of showing.

Humans are rather finite–we can only take in so much of something before what we already have up in our noggin starts to leak out when we try to put more in there. This is why initially a quest log may seem appealing for both the game player and the designer. “Oh boy, I’ll never forget what I need to do!” says the player. “Oh boy, they won’t get frustrated from not knowing what to do!” says the designer. The truth is, if your game relies heavily on a quest log, there’s probably something wrong with your game.

You see, if your (designer’s) quest is worth making, the player should want to finish it whether the game is telling them to or not. It won’t matter if it’s game-critical. It won’t matter if they get a reward. Your player will look at it and say “I want to do that. I need to know what happens from that. I need to discover that,” and then they will go out and do it. They don’t need to be told to do something. They shouldn’t be told to do something. A player doesn’t turn on a game to be told what to do, a player should turn on a game and be inspired by it to the point where they want to go out and do those things on their own. A player turns on a game to discover a new world for a little while–to be shown a world of adventure, not be told about it. A quest log is nothing more than a to-do list. It bleaches all the fun out of the game by removing any and all forms of self-motivated discovery. It immediately divides all information the player is receiving into two kinds of categories: information that I can get something from and information I can’t get something from and they will never have to think about which is which.

Hear a story about a drunken bartender? Well, it didn’t get added to my quest log, so it’s worthless. Vague mentioning of some kind of gem that I wasn’t really paying attention to? Immediately got added to my quest log in addition to where I need to go to find it, so it must be important. I cannot stress enough how bad of a mechanic this is–how horrible a method of player dictation this is. You’re literally telling the player what they should think is interesting and uninteresting instead of showing the player what is interesting and trusting them. As a designer, you need to have enough confidence in your creation that the player will want discover the things they think are interesting on their own. Quest logs simply cater to an audience that is too impatient or too stupid to invest themselves into something.

What’s worse is that it ruins the game’s immersion. Players feel this constant pressure to be accomplishing quests and if they aren’t following the pre-laid footsteps of a quest’s pathing they feel as if they aren’t accomplishing anything, which is criminal. A player should feel like each step they take into the unknown is accomplishing something. They should feel that each creature they slay, big or small, hard or easy is a worthy task. Quests logs instead make the player switch “quest on” and “quest off,” which takes away any need the player’s need to think. Players immediately know when a quest ends if it finishes in their log. They know when a quest begins when it gets entered into their log. There’s no uncertainty or anticipation or ability to make your own decisions concerning what you as a player think is worth your time.

When we slay the Talamar at the college, we know he’s dead because the quest told us it was finished. Imagine if the game didn’t tell us–we might be confident that things have wrapped up or we might think, “What if he comes back? What if he finds a way to seek revenge? Is this truly the end?” When we defend a stronghold from the damn rebel scum (because Ulfric is a dick and no one should side with him) we immediately know when the attack is finished and when we can just completely drop our guard, because the quest told us so. We don’t have to think “what if there’s another attack” or “maybe there is a remainder of the guards that I missed planning to sneak in?” No, it’s just a flip to your quest log which says “Yup, you killed all the things, now go back to a camp so you can go to another X,Y coordinate and kill more things.”

Skyrim isn’t the only game that suffers from this, but just consider the effect it has on the world. Reading anything in the game is no longer a method of uncovering the mysteries of the world internally–if what you were reading was important, it gets added to your quest log. Otherwise, you can just throw it away and forget about it. Rumors or stories that you hear characters say are immediately forgotten if they don’t trigger a quest. What’s the point of remembering them? Emphasis in the game isn’t placed on discovery or morality or even just a decency to help people–it’s replaced with getting the blasted check box in your to-do list marked off so you can get your reward and move on to the next one! Any thing you discover in the world–anything that isn’t quest related or doesn’t have a reward attached to it–immediately feels less valuable in this kind of system. All the little detail in Skyrim is overshadowed by the desire to follow the pattern of “do thing, get thing.”

Players want to do something interesting. They want to go on an adventure–they want to change their world and they want to grow stronger. If all of the quests in your game are so numerous and so forgettable that you feel you must rely on an auto-filling quest-book to motivate the player to do them, then you should have never made them at all. A player who is inspired by your world will find something to do on their own. They will remember the things that interested them or excited them and they will venture out into the fantasy world to be their conqueror. Once they’ve completed the things that interested them the most, if you did your job right, they will hunger for more and dive back into the collection of interesting things you’ve set up for them to do. You need to let the players choose what they care about and what they deem worth their time. A quest-book sends the message to the player that they have to do everything. They have to do all the chores and if you’ve played Skyrim for more than a few hours, you really start to feel like all those quests piling up are just that–chores. Frankly, if your quest wasn’t interesting enough for the player to remember and complete on their own volition, it’s either because they were too busy being engaged by some other awesome quest that you put into the game (which is a good thing), or because your quest is refuse and is so forgettable that it isn’t worth anyone’s time.

Level Scaling

This is the greatest sinner of the bunch, and it’s probably the most mechanics heavy. Level scaling is the DEVIL. Like, if I die and go to Hell, there’s going to be two things going on. Number 1: I’m going to be in my horrid Walmart uniform stuck at a checkout lane forced to listen to the endlessly repeating commercials on the TV above me and Number 2: every time I get better at some aspect of checking out my customers, something will happen so that my improvement is completely removed. My job will be just as hard as when I started, meaning that my accomplishment meant nothing. Taking a look at the latter, the sad part is, is that’s essentially what game developers are telling you when they make their game’s level scale–you have accomplished nothing. In fact, in some cases, level scaling can create the phenomenal effect of your strength going backwards.

I’ll use a simpler example than Skyrim to show what I mean. Secret of Magia also used level scaling. Admittedly, Secret of Magia is one of the worst, under-designed, non-fleshed out piece of crap games I’ve ever played, but avoiding all of that and looking directly at its level scaling system, it exhibits level scaling’s fatal flaw perfectly. Every time you level up in SoM, every single enemy levels up with you at a fixed and uncapped rate of growth. Since the growth rate is fixed and since the stats are built up the same from level 1, if you disregard your character’s equipment, a fight against a monster at level 1 would be identical to a fight against a monster at level 5. The problem is that when you add in equipment, it becomes a whole new beast.

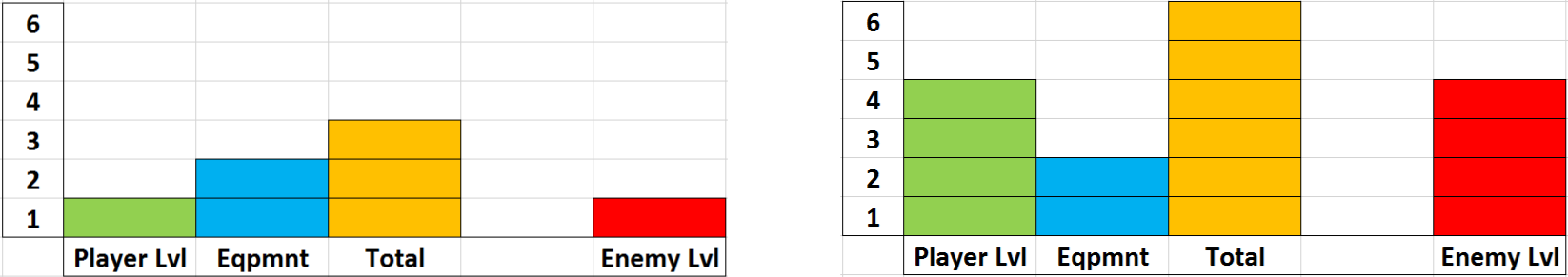

The first graph here is a simplification of the player’s power in relation to their level and equipment, versus a monster’s power based on level. As you can see, a level one player with enough equipment to equal two more level’s worth of stats would match up against a scaled enemy with a ratio of 3:1, or 300% power over the enemy. Now let’s add 3 more levels to our player, keeping the equipment power the same because equipment does not scale with level. Now instead of a 3:1 ratio, we have a 3:2 ratio or 150% percent power over the enemy. As you can see, in this instance gaining 3 levels actually cut our character’s power in half which is ridiculous.

Skyrim, (and any game with level scaling really) while more complicated, functions in much the same way under the same principles with an additional few aggravations. The same problem with equipment persists, in that because equipment does not scale and considering that half if not more of the enemies in the game do not wear gear (and I’m not even sure if humanoid enemy’s equipment are actually even factored into a monster’s stats) leveling up still makes you weaker against enemies that scales with you. It gets worse though when you add perks to the mix. The perks on their own are not bad–a bit bland, maybe, but in and of themselves they are not the cause of the problem; the level scaling is. You see, by choosing a non-combative perk, you create the same problem as the equipment dilemma. Want an easier time picking Novice locks? That could have been an extra 10% damage on your axe swing, or it could have been halving the cost of your Adept Destruction Magick, allowing you to cast more spells to deal more damage. By picking the Novice pick lock skill, you are no stronger (aside from the 10 points in HP, MP or Stamina) than you were a level ago, but the foes you face will be one level stronger.

What’s even funnier is how Bethesda tried to band-aid fix this problem. It’s clear that someone in the studio caught wind of this problem and wanted to do something about it but the final product just creates a different problem. You wouldn’t necessarily figure it out just from playing the game, but Skyrim has tiered difficulties for certain enemies and dungeons. They essentially have caps both at the bottom and top of their level ranges so that even if your level is lower or higher than theirs, their level cannot be lower or higher than a certain defined integer. To further muck things about, they also decided to that certain tiered enemies wouldn’t show up until the player was a certain level either. For example, Dungeon ABC contains Bandits and Skeever. The Dungeon itself has a level range of of 10-30. This means that if you go into the dungeon below level 10, all enemies will be at least level 10. If you go into the dungeon above level 30, dungeon enemies will only be level 30. Enemies themselves have their own individual level ranges as well–for instance, maybe the Skeever’s is level 10 while the bandit’s is level 30. This means that Skeevers in the dungeon will always be level 10, but if the player enters in at a level higher than 10, the Skeevers will still remain at level 10. The bandits might be a different story though, since they might have tiered bandit archetypes. At level 15, the “Bandit Ruffian” might appear, and at level 25 the “Bandit Chieftan” might appear.

While in theory, this sounds all fine and well, it’s not in practice. As stated, it is a band-aid solution at best which just introduces different problems. Enemy power rankings are still completely variable with no indication to the player what kind of strength the foe they are facing possesses. A level 1 player who a little while ago was happily killing the level 1 scaled Skeevers near Riverwood may stumble into this dungeon and suddenly be beset upon by murderous level 10 Skeevers that look and act identical to the ones he was fighting previously. A level 24 player may run around the dungeon feeling quite powerful, but a level 25 player will enter the dungeon and struggle against the difficulty spike created by the introduction of the new Bandit Chieftan. Once again, by gaining levels the player is punished with absolutely no indication or warning to the player to the contrary, save for a different enemy text name, one that certainly blends in with all the other tiers of bandits that they’ve likely been encountering.

Developers need to get rid of level scaling forever. It creates complete chaos and inconsistency in the world. The player has no real way of knowing what to expect when they enter into a dungeon–but not in a good way. It’s true, as a general rule, the dungeons around Riverwood are a lower level–but this is just a general rule, and it hardly has much of a pattern outside the Skyrim’s beginning area. The developers delved too greedily and too deep; they pridefully tried to create a game that was completely accessible to low level players while still maintaining some semblance of matched difficulty to the player’s power. Instead what they created was an inconsistent mess that rides wild and unpredictable difficulty spikes that ultimately peter out at around level 40, where at that point most of the dungeons are either relatively scaled to the player power or laughably easy.

The fix for this? Keep the damned enemy’s power level consistent you morons! Quit being afraid that if your player doesn’t have access to each and every location in the game right away that they’ll start whining and quit! With level scaling, there is no progression! It takes as much effort to kill a mammoth at level 5 as it does level 25–why did I even bother gaining the 20 levels in between? It’s no wonder I feel empty inside when I clear out another dungeon, because I know that the game gave me a lukewarm challenge that was tailored to my skill level. There’s no need to be afraid or concerned when walking into a dungeon since I’ll always know that it will be scaled to my level–except when the dungeon’s lower level cap is 20 levels higher than me and I’m getting ROFLstomped by bandits and wizards that look identical to the level 1 bandits and wizards I was fighting in the last dungeon! Just make things consistent in power level–make the giants these foreboding doom-creatures that it really means something when you finally get the ability to kill them. Allow a low-level player to slay smaller spiders with relative ease, but make the massive ones truly deadly!

Once the world becomes consistent to the player, they can begin to gauge the power of the things they are facing in relation to their own power. They can begin to understand which dungeons are heavily guarded and which ones are simply filled with bandit rabble. This kind of balance usually leads to a stronger community base since you have speedrunners and game-breaker enthusiasts banding together and asking each other “Just how can a level 1 creature sneak past the troll?” or “How can I get my level 5 wizard to kill the giants guarding the cave that’s meant for high-level players?”

By creating level-scaling, players will never feel accomplished because they never know what to expect. Enemy names, types and even the models themselves almost become meaningless since they won’t know how strong something until they give it a wack, even if it’s the same monster they’ve encounter time and time again. Level scaling is nothing more than a cheap method for the developers to try to instill an artificial feeling of “balance” in their game, when really all they’re doing is washing their hands free of any kind of progression design or real balance, not to mention the complete way it breaks immersion when I’m never afraid to go anywhere or fight anything at level 1.

Combat/Equipment/Balance

Herein are miscellaneous complaints that are worth mentioning, but are not necessarily large enough to require an entire section devoted to them.

Melee Combat in the game is incredibly simple–horribly so. If you are a fighter, it’s swing, swing or swing. You might occasionally block, you might charge up a swing, but in the end, it’s just swing or be swinged.

Archery Combat consists of clipping enemies on rocks or trees and then filling them full of an inordinate amount of missiles while they stand there staring at you.

Magic is a let-down. Not only are spells lackluster, but they are rather barbaric in their straight-forwardness. Lightning is laughably useless unless the enemy is using it on you. Frost is ok, but not really worth it in the face of Fire’s DPS. The starting fire spell is one of the most efficient DPS spells in the game, especially if you stutter cast it, which isn’t even a bug–it’s simply a method of conserving mana while maintaining the same level of DPS. You never truly feel like a powerful wizard, no matter how many points of destruction magic you have. Healing magic has a similar problem–the starting healing spell is the most efficient; why bother using anything else?

Equipment is a joke. Medium armor is pointless–light armor is somewhat useable, but once fully perked there is almost no disadvantage to heavy armor for any character. Since classes don’t exist, any character can wear whatever they want. No need to use your brain when equipping things either since everything is a binary progression up to a higher number for defense. Glass armor will always be better than steel. Steel will always be better than iron. The armors are nothing more than numbers.

The problem mentioned earlier concerning equipment not scaling in relation to the player’s level can actually be abused by players focusing on equipment crafting, giving them an incredibly powerful but artificial power boost. Coupled with enchantments allowing magic to be cast for free in addition with the lackluster scaling on spells means that a player wearing armor that lets them cast spells for free will be nearly as powerful as a wizard who has spent all their perks into magic.

Enemy wizards are extremely broken. At this point, I have played several different types of characters and put my stat points into several different areas. I can tell you that if you play as a wizard, you will never even come close to the strength possessed by enemy wizards. Likewise, in a playthrough where I put every single point I had in HP, I was one-shotted at full ~300HP health by an enemy wizard who was using the level 1 lightning spell.

The only time you will be “challenged” by an enemy in Skyrim is when you face one that can one-shot you, or very nearly so. This isn’t really a challenge, since such an occurrence offers little to no counterplay. Additionally, because of the relatively shallow battle mecahnics, any other kind of fight in the game is brainlessly winnable for several reasons. 1. You probably have enough potions to health-spam your way through an enemy. 2. If you need to, you can just heal with your MP. 3. You probably have enough MP potions to MP-spam your way through an enemy or 4. You probably have enough MP potions to MP-spam-heal your way through an enemy. 5. You can probably just run away and shoot an enemy to death with magic and/or the 1000+ weightless arrows you’re carrying. 6. If you get really desperate, you can eat all that odd food you’re probably carrying from when you accidentally picked it up earlier. 7. You probably have an essential ally that will never die with you that you can use to face-tank. 8. If all else fails, you can just run away, heal and come back again. It’s not like the enemies are going anywhere, or your quest has a time-limit.

Dragons are laughably easy to kill.

Dragons can laughably easily kill you with their instant-death chomp regardless of what level you are.

Dungeons have burning torches and fresh fruit.

The majority of the game’s treasure is randomly generated, making everything you get feel like random code and not a unique piece of equipment.

Fast Travel sucks because it takes all the excitement of traveling away. Walking from place to place sucks because there’s nothing interesting or valuable to discover along the way.

I think that’s enough for now.

In Closing

Skyrim is an awful game. It’s mechanics are pure garbage, and its immersion suffers heavily for it. Skyrim is the only Elders Scrolls game I’ve played, which makes me sad because all through my life I’d heard good things about the franchise. So I leave you with one necessary and crucial piece of information that will help cement what you’ve read here, as well as what you know about me as an author let it be known: Skyrim is a disgusting puddle of sheeple worshiped fan-hype…

…that I have put 375 hours into because mods are @&$%!*# amazing.