I suppose it was inevitable that I’d be rolling a lot of big series in my Steam lottery. I have many, many games that are part of a series that I haven’t played. Mostly, I held off because I like to start at the beginning of a series, and the first game is usually not that great (I’m looking at you, Final Fantasy. And Ultima.). This time, it’s Tomb Raider and the various adventures of Lara Croft. I have now tried all the PC-released Tomb Raiders (except Rise of the Tomb Raider. Don’t have that one – though I’ve heard good things). There’s a lot to say here, but I’ll try to keep things moving quickly.

The Tomb Raider franchise is one of the most well-known of video game franchises, and Lara Croft is perhaps the most famous female video game character thus far in gaming history (competing with Princess Peach, Samus Aran, and Cortana). The PC releases of the franchise can be broken into three categories: the originals – built on the classic engine, the Legend chronology – built on the Legend engine, and the modern era – a hard reboot from 2013.

Tomb Raider, Tomb Raider II, Tomb Raider III, Last Revelation, Chronicles, Angel of Darkness

Why, you might ask, are all six of these games grouped together? It’s because I’m cheating a bit. I’m lumping all of these into the “Technical Issues” category – though not because the games didn’t run on my computer. They’re being shuffled to the side because I just could not get the hang of the controls. Between not having mouselook and Lara turning and jumping crazily, my ability to play these games is almost non-existent. Back when they were released, I’m sure I would have put the time into learning the controls – but today? I’m content to just look for a fan mod that makes it easier to play. I do want to comment on my (limited) experience, but that will wait until my discussion of Lara herself.

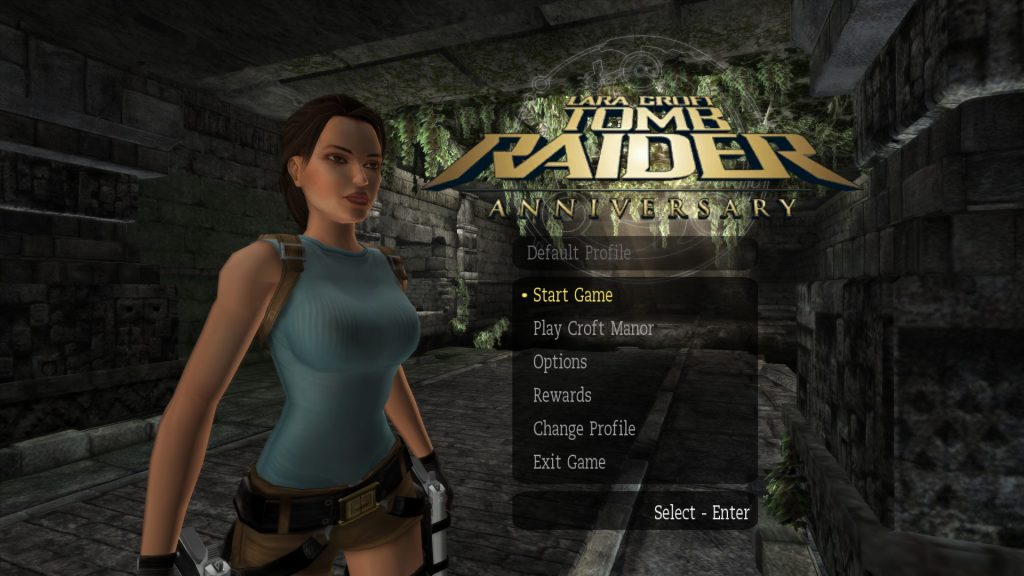

Tomb Raider Legend and Tomb Raider Anniversary

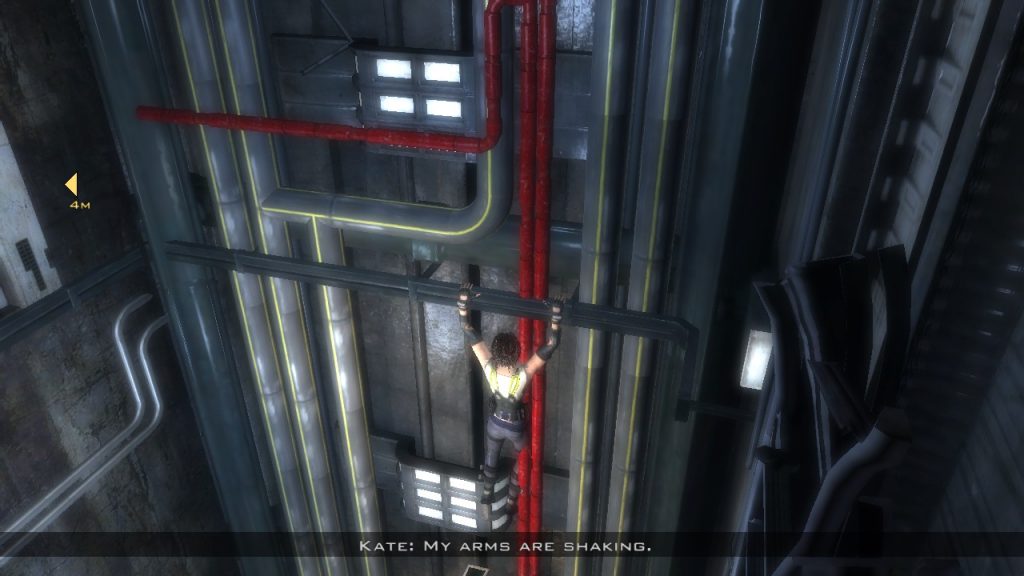

These two games marked the first soft reboot of the series and a long-overdue move to a far superior game engine. Both of these games go solidly into Tier One – Legend is the only game I played longer than I force myself to – and Anniversary seemed on par. The platforming isn’t as terrible as in previous games (or future ones, for that matter), Lara is still a strong protagonist, and her legs are composed of more than three polygons. The set pieces are fun (even though I did get a bit lost). Near the beginning there’s an arena that I got stuck in for about ten minutes while I tried to find my way out. That brings me to the two problems I had with this section of games: puzzles aren’t always clearly presented, and climbing is a bit tricky (and not in a good way).

My complaints wouldn’t be such a problem except that puzzles and climbing are the bread and butter of the Tomb Raider franchise. While it kept being fun, I found myself wishing that these games had the puzzle-presentation of Valve with the free-running of Assassin’s Creed. There’s a bit of advice (I don’t remember where I first heard it) about puzzles: it stated that a good video game puzzle is one that you have all the pieces to. In Tomb Raider Legend, there’s far too many instances where a puzzle relies on a small hidden door or switch – this is acceptable from time to time, but it breaks the flow of the game when it goes on too long. Similarly, climbing is limited to very specific (and often unclearly marked) ledges – which makes the navigation part of the game that much more obtuse.

Nevertheless, these games were fun and kept me interested and playing. In fact, Anniversary (a re-imagining of the first game with the engine of Legend) had that ineffable “good” feeling you get when playing a game that is just plain fun.

Tomb Raider Underworld

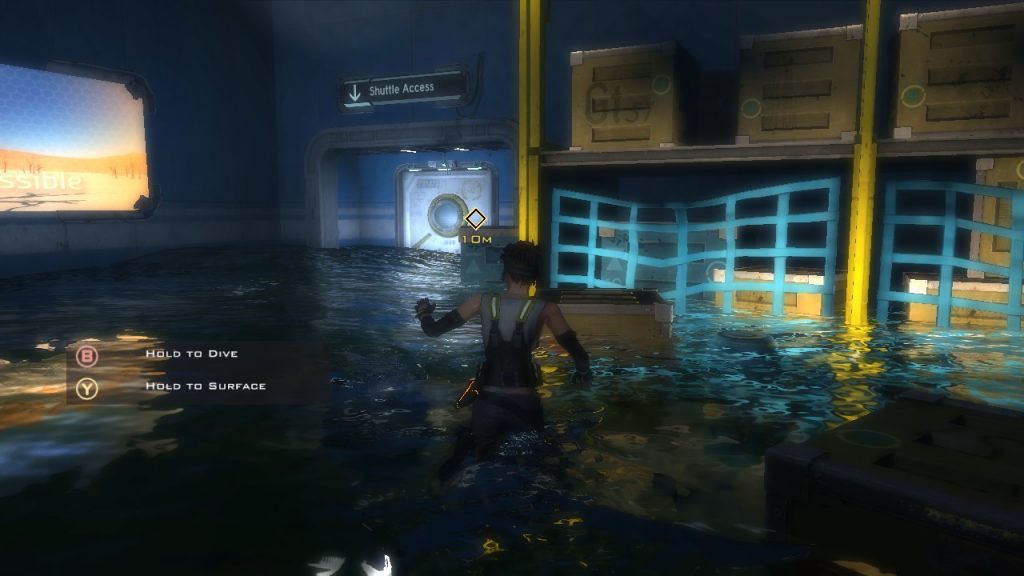

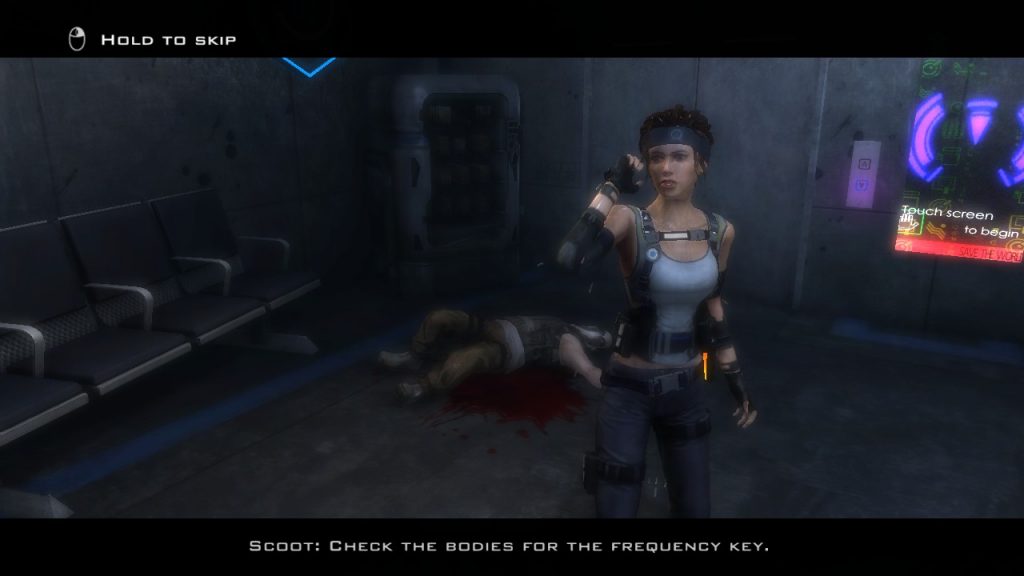

Those of you who have played the Tomb Raider franchise may have noticed I left off one of the Legend engine games: Underworld. This is because it goes into Tier Three, unlike its predecessors. It goes into Tier Three for two reasons. First, the camera and movement. While Legend and Anniversary’s camera control was reasonable, Underworld’s camera and Lara’s direction of movement will only occasionally follow your command.

The second problem comes from the ridiculous and contrived plot – which is a remarkable complaint when talking about a Tomb Raider game. But as you see above, one of your first tasks is to murder a giant octopus. Typically, it is best to descend slowly into strange worlds: slowly revealing more and more unnatural things. Underworld pays little mind to this – or to reason itself – preferring to have a plot that progresses because there wouldn’t be a story otherwise. Why do you kill the octopus? No particular reason. Why do you call your team before diving to the underground city? No reason. How do the “bad guys” show up immediately behind you with no warning and entirely silently? Because there wouldn’t be as much plot otherwise. This seems to be a theme throughout the game – trying to “raise the stakes” just results in an unbelievable story.

Tomb Raider

Finally, we come to the most recent reboot. I don’t have any pictures for this section since I actually beat this game a year or two ago. Since it is part of the same series, I thought I should talk about it briefly here. This also gives me the chance to put a second game into Tier Four. I recently talked with Chezni about Tier Four, and it turns out we had different ideas about what it meant. The definition on the rules states that Tier Four games are not worth the time put into them. I had taken that to mean the time spent to play them was entirely wasted, while Chezni saw the definition as saying that the game itself was not worth the time spent developing it. I like that definition more, and it is the definition I use here.

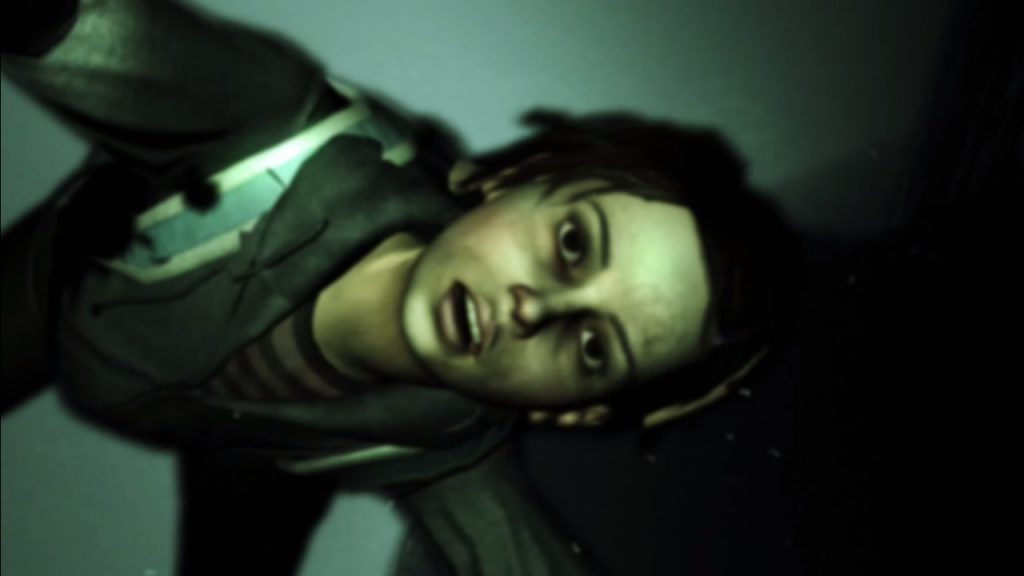

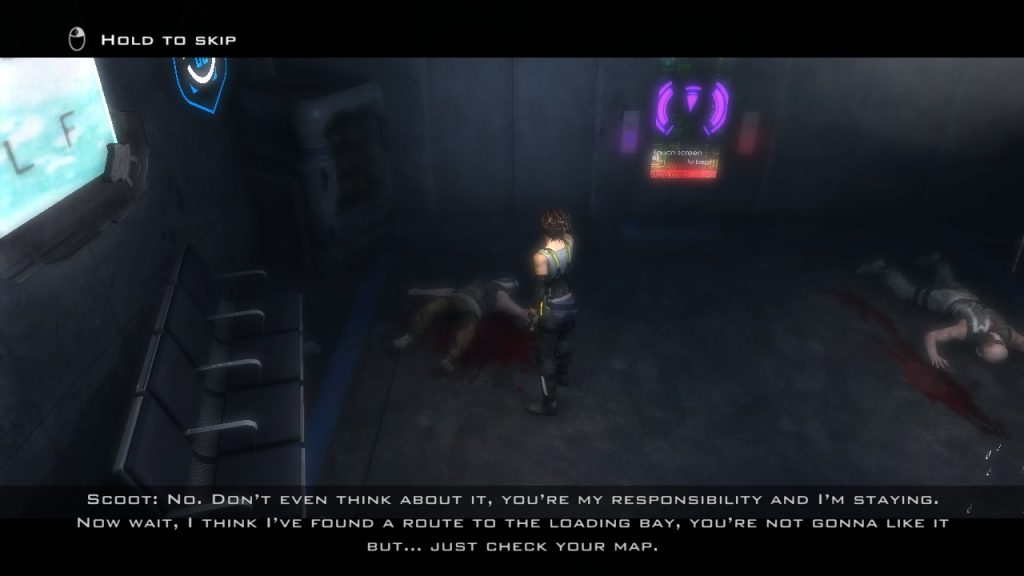

So why does the Tomb Raider reboot go into Tier Four – particularly given the large number of accolades it received? It’s not because it uses the most cliche of plots (with Nazis and supposedly sympathetic nerds sacrificing themselves for no good reason). Instead, it starts with quick-time events. Quick-time events pervade Tomb Raider and its cutscenes – these replace gameplay with a punishment for not knowing exactly which buttons to push. This is apparent challenge without real challenge, and they only exist to give the player a feeling of accomplishment for doing something cool during what might as well be a cutscene. And if you fail? You run into the next problem: the unreasonably gruesome deaths of Lara Croft.

Lara Croft will die in the most horrific and terrible ways – for no good reason (quite often that you hit the wrong button during a QTE). While playing the game I could only guess that the game designers really, really liked blood and watching people die. Recently, I was talking with Chezni and he mentioned that the producer wanted it this way to inspire the player to want to protect Lara – which certainly explains some things (more on that later). I have no problem with gore or violence. I have a problem with pointless gore and violence. Think about the time the developers spent on animating Lara getting eaten by dogs, impaled by spikes, and nearly/probably raped. Think about the time they could have spend making more places to explore. Get mad.

Finally, we have the biggest problem – at least gameplay-wise. There are mini-temples and crafting mechanics throughout the game, but no motivation to actually use them. I finished the game without finishing a single side-dungeon – and only actually finding one. The game is designed to trick you into thinking you have a whole island to explore. But really, you just follow a set of linear quests to the end of the game. Admittedly, I did not take their chances to explore the island – for the reason that at every point in the main quest-line, you are given a sense of urgency to complete the next mission. I took this to mean that perhaps Lara would return to the island after finishing the plot and give you time to go find all the nooks and crannies where treasure might be hidden. It did not. The Lara in this game would likely never return to this island even if it contained the most fabulous treasures in the world.

Lara Croft

Lara Croft is a difficult character to analyze, made more difficult by the four distinct takes on her character. The Lara Croft of the first six games, the Lara Croft of the Legend trilogy, the Lara Croft of the reboot, and the Lara Croft of the movies are all distinct. Perhaps the best way to describe her influence is controversial (I promise I wrote that before reading her Wikipedia article). On the one hand, all but her most recent portrayal has been as a devil-may-care action hero. On the other hand, perhaps her most famous physical feature is her remarkable pair of…eyes. And if you played video games in the ’90s and early 2000s, it was almost impossible to avoid the seemingly endless supply of nude mods for the Tomb Raider games. Though, on this last point, I’m not sure we should judge a character based on what is done to them by the internet – Rule 34 exists for a reason.

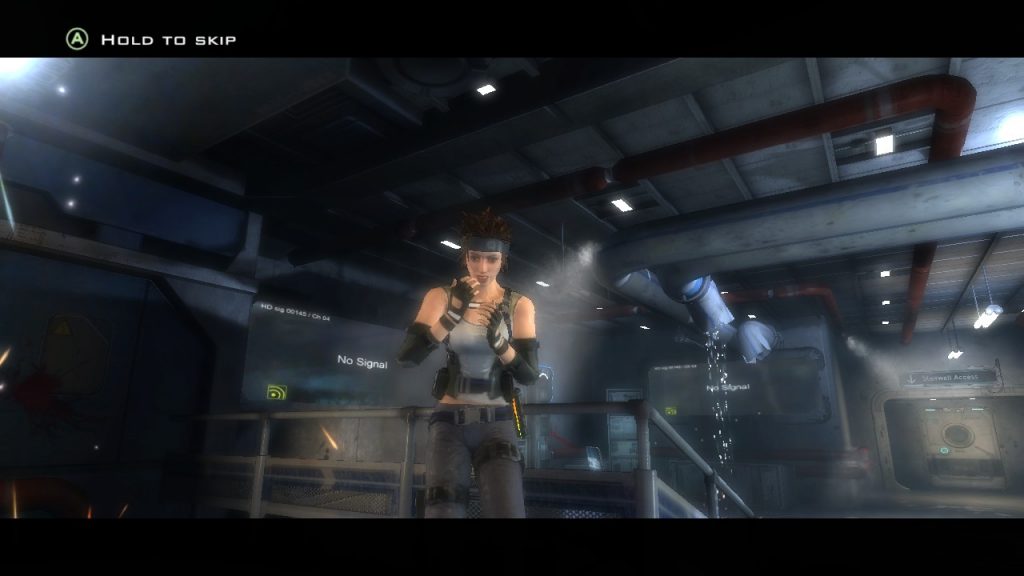

We are faced with two aspects of Lara Croft that diminished as the series progressed: body proportions and sassiness. Earlier iterations of Lara were entirely unrealistic, but she also commanded an attitude of control and confidence – approaching a level rivaling Saints Row. The Legend games toned down both her unrealistic proportions and her remarkable attitude. I think this was probably the sweet spot for Lara as a character – even if it was still on the side of unrealistically proportioned. An action hero can be unrealistic both in character and in body, as long as neither are taken too seriously. At the same time, this must be balanced by believability if you want to start telling a complex story. This toning down continued on both fronts into the reboot – and Lara became yet another bland protagonist for people to project their fancies on.

The Lara of earlier games is an action hero in the style of Bruce Willis in The Fifth Element or RED – ridiculous, over-the-top, and a bunch of fun (if a bit questionable on occasion). This is important because these elements are so diminished in Underworld and non-existent in the reboot universe. In attempting to make Lara more realistic, they made Lara less Lara.

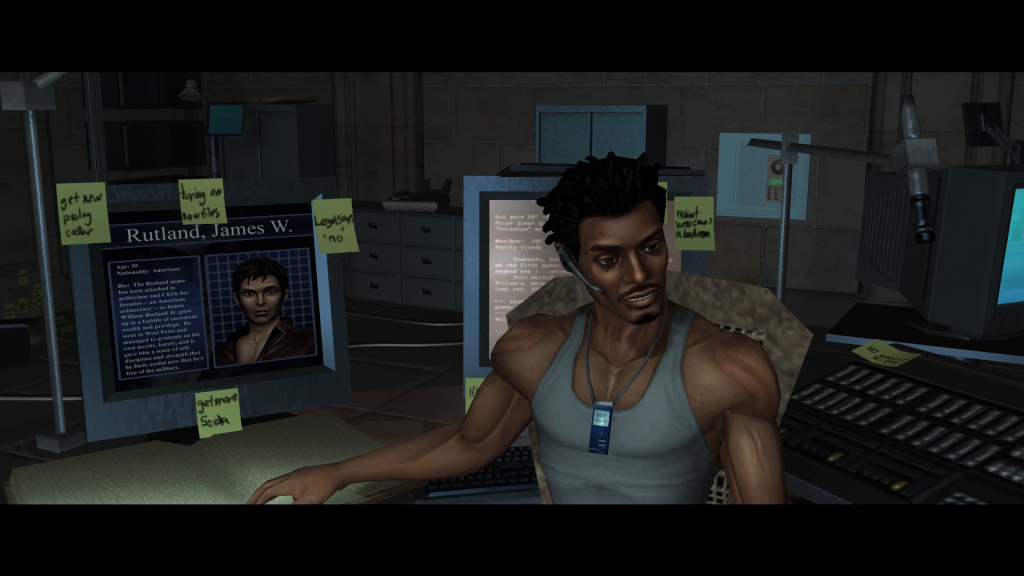

Oh well. At least the developers of Tomb Raider don’t care about body proportions regardless of gender:

Steam Link